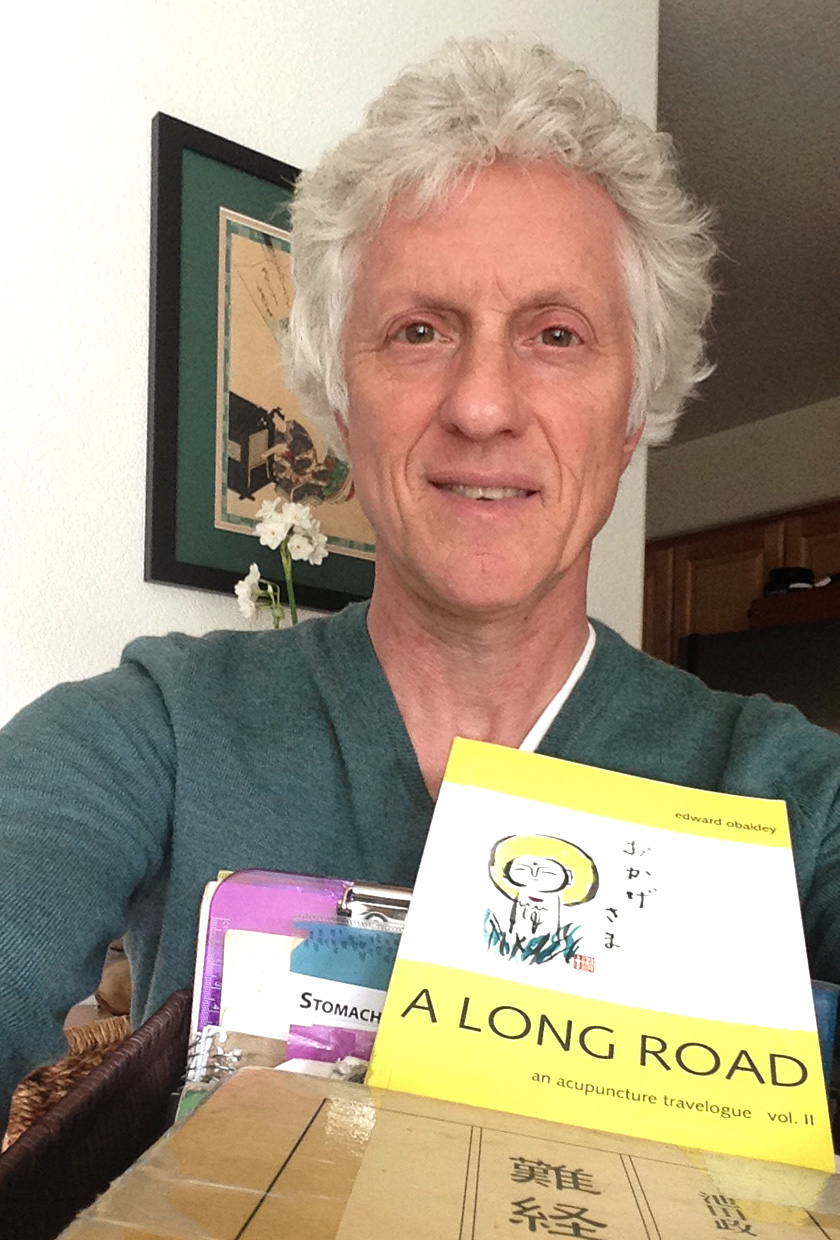

My teacher, Edward Obaidey, who has been practicing, writing a series of acupuncture books, and translating acupuncture texts, all while maintaining an extremely busy practice in Tokyo for the past 25 years, has been a great source of inspiration. He has instilled the “need” to study the major classics, to penetrate the essence of our art. The “need” was compulsory, this was a baptism by fire. I resisted and it was very difficult to grasp. Over time, my resistance faded and has morphed into a burning desire, pun intended! You see, out of 10,000 books extant about Chinese medicine, less than 1% have been translated into English. There are numerous texts that have been written and translated about this medicine but a picture is worth a 1,000 words. Literally speaking, Chinese and Japanese are logographic languages. Through these pictographs, meaning unfolds and speaks to us in a way that is greatly diminished when written in English.

Let’s take a look at what my teacher wrote about an acupuncture point named Bladder 40, as illuminated in his book, A Long Road Vol. 2.

I Chu (委中, BL40): Tight Knees and Lower Backs

The point I Chu (委中, BL40) is written with the character “委” and the character “中”. The first character can be broken down into parts, upper and lower. The upper part, 禾, can mean a rice stalk bending with the heaviness of the ripe rice ready for harvest. The lower part, 女, is the character for female adding a further aspect of flexibilty and gentle compliance. In a general sense it can also mean acting not from oneself but letting things take their course or going with the flow.

The second character, 中, means “central” or “middle”. Taken together then we can see that the point actually tells us about the nature of the legs. The legs should be flexible, resilient and bow gracefully under load. The point I Chu is the point at the back of the knee where the bending occurs and this is located at roughly the mid point of the legs thus the character for “Chu”, the middle.

We all know that I Chu is essential for treating knee and lower back problems of various types. We can see from our clinical experience that for most chronic problems I Chu will be hard and lacking in resilience with pain upon pressure. In a healthy state we know that it will be soft, resilient to the touch and does not display pain upon pressure. From all of this we can infer usage of the legs. When bending the legs at the knees we should concentrate on letting I Chu relax to let the load go through the knee into the feet and deep into the ground. It does not take an active role in weight transference and simply lets go.

I remember the day when a big box of books arrived at my teachers clinic, in Tokyo. We opened the box which contained about a dozen copies of the Nan Jing, translated by Masakazu Ikeda, my teacher’s teacher, one of the most brilliant acupuncturists in Japan. It was not only a translation but contained clinical commentaries, by Ikeda sensei, which flesh out the passages. For my teacher, my fellow students and myself, it was a revelation of a sacred text. My eyes were like saucers, the depth palpable without cracking the book open. The Nan Jing, which means “difficult issues”, was written about 1,800 years ago and has 81 chapters. The book is divided into the following sections: illnesses, pulse diagnosis, the five phases, treatment and yin/yang theory. The clinical viability gleaned from studying this text, as well as other classics, is well worth the effort.

There are many styles of acupuncture practiced in the world, so you could say I practice a Japanese approach that is based upon the Nan Jing, as taught to me by Edward Obaidey and his teacher Maskazu Ikeda.